Hong Sang-soo is in a peculiar position. His last few features have explored the same tragicomic universe, involving the same constellation of married professors, struggling directors, and empty soju bottles. Working only within this small, circumscribed area, Hong surprisingly never comes across the same place again and again. He traverses this world microcosmically like Budd Boetticher in his Ranown cycle: the slightest modification unveils a hidden realm. New corners, new spaces, and new modulations are discovered repeatedly in his repeated worlds. His films may be micrometers apart from each other, but Hong makes the tiniest differences resonate. On the razor edge between a remarkable consistency and a tiresome monotony, the ease with which Hong has steadied himself on this privileged but precarious spot is nothing short of impressive.

Our Sunhi is Hong’s most straightforward work since his 2009 short

Lost in the Mountains. A simple prototype from which Hong’s more complicated narratives derive from would probably take the form of this film. After the reveries and bereavement of

Nobody’s Daughter Haewon, Sunhi strikes a lighter tone, forgoing structural games for thorough observation. With plans to study abroad, Sunhi (Jung Yumi) returns to the university she had abandoned years back to ask for a recommendation letter from her former film teacher Professor Choi (Kim Sangjoong). During this time, she bumps into her old flame Munsu (Lee Sunkyun), who is now an unsuccessful film director, and Jaehak (Jung Jaeyoung), a college senior who recently left his wife. Sunhi soon becomes an emblem of desire for these three men: they all want to know more about her as much as she wants to know more of herself.

Loss and mourning permeate the world of

Haewon, while aimlessness and dissatisfaction infuse

Our Sunhi. Part of the humor of this film comes from the characters appeasing one another for their personal failures or lack of direction. Sunhi, after closing herself off from the world, is only recently coming out of her shell, and most of the conversations, initiated by the male characters, concern the qualities which make Sunhi special. The men aim to define her best features and characteristics, in hopes of boosting her confidence and possibly winning her heart. However sincere their reassurances are, throughout the film these inebriated Romeos remain suspect. There hangs in the air the painful possibility that their words of wisdom, so dear to Sunhi, are nothing other than feckless clichés. The evidence is in the overload of repetition. Unconsciously, the men begin to repeat each other’s words, insights, pieces of advice; they sometimes mimic each other’s gestures. Characters seep into each other. The logic of déjà vu appears once more in a Hong film.

Different characters carry out the same acts. The direction spills them onto matching situations. Minute details echo around them. Some cross the same pedestrian lane, others call out to the same balcony, and everyone finds themselves intoxicated inside the same dive. Fried chicken mysteriously pops up whenever they are drinking. Scenarios are modified minutely in their duplication, with the shuffling and reshuffling of characters, settings, and objects providing the subtle difference. Adding more resonance to this set-up is the recurrence of Hong’s stock company of actors roughly playing the same roles as the director’s previous films: Jung Yumi and Lee Sunkyun are a couple in

Lost in the Mountains and

Oki’s Movie, while Kim Sangjoong is a film critic in

The Day He Arrives. A series of basic two-shots, consisting of characters facing each other across tables littered with booze, becomes the main building blocks for this mixture of textual and extratextual déjà vus. In its endless variations and rearrangements of the two-shot, the persistence of which allows the smallest subtleties to be palpable,

Our Sunhi resembles a mad game of musical chairs.

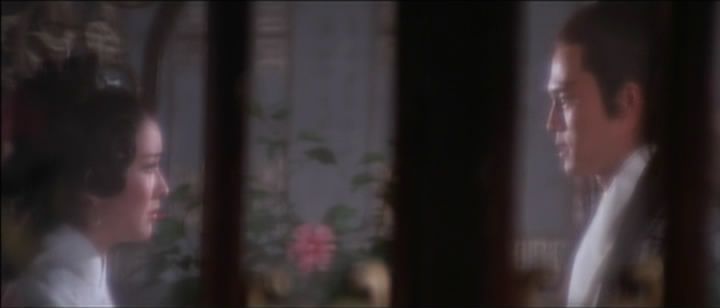

Save for his trademark zooms, Hong’s two-shots are cemented in a rigid framing, taking up long stretches of time. A barebones approach to composition assembles persons, tables, bottles, in an uncomplicated mise-en-scène. Only few things of interest fill up the frame, which would be seen as empty if Hong did not hold its duration. Lav Diaz once mentioned that long-take aesthetics enabled the spectator “to see beyond the image”. Hold an image long enough and the spectator starts sensing the presence of associations absent from the image. For Hong, the tension of time allows his almost vacant images to brim over. Observing performance, gesture, and dialogue with an unwavering curiosity, Hong lets the unseen threads running through the fabric of the film emerge through the prolongment of the two-shot. Threads of narrative detail, character history, and structural echoes are the intangibles always filling up the wide gaps of his compositions. Only within these empty spaces, it seems, can the unconsciousness of the film find a spot for itself. The image thus turns into a breeding ground for narrative guesswork, absorbed contemplation, and future speculation --- a projection of possibilities “beyond the image”. Hong’s two-shots become wells opened through time in which the wounds of the past, the pressures of the present, and the uncertainties of the future, fill up a capacity that never runs over. A cloud of possibility hangs over two bickering drunkards framed in the most rigid of compositions. An airtight mise-en-scène becomes porous.

These possibilities also unsettle the stillness of the two-shots. In a dialectical movement, these scenes pulsate as they remain motionless. Character tensions smolder and shoot off embers while the camera freezes up to feel the burn. At this moment Hong’s famous zooms usually appear, following the emotional ebb and flow crisscrossing between his characters.

Our Sunhi, though, uses zooms sparingly. Zooms in

HaHaHa or

The Day He Arrives guide the spectator into the subtle drama of its scenes; the zoomlessness of

Our Sunhi unmoors the spectator onto a free-floating drama filled with unresolved details. Hong allows the drama to unfold without interference, and without the guidance of the zooms the spectator can get lost in the flood of narrative detail that fills up his demarcated frames. In Hong’s previous films one is guided, in

Our Sunhi one drifts.

Narrative detail reshuffles, reshapes, unsettles, scenes once it floods in. Hong’s minimal mise-en-scène channels in this deluge. This onrush continually modulates the tenor of the scenes on a moment-to-moment basis. Déjà vus usually set this modulation in motion. In an eleven-minute shot with little to no camera movement, a drunken conversation between Sunhi and Jaehak (the two characters who have shut themselves off from the world) seems to be unraveling the inner dilemmas of both characters. The scene moves from reserved flirtation (Jaehak regularly flicks Sunhi’s hair) to all-out affection (Sunhi lays her hands on Jaehak’s face). And yet the tenor changes when Jaehak starts repeating unconsciously the monologues of Munsu and parts of Professor Choi’s recommendation letter. To complicate matters, bookending this scene is the déjà vu of the bar hostess’ call to order for chicken and its eventual delivery eleven minutes later, as if the entire scene was a comedic pretence for waiting for the deliveryman to arrive. The same trot song from previous scenes returns once more. Nothing remains settled in the simplicity of the scenes. In

Our Sunhi, Hong composes closed spaces in which narrative, character, tone are always shifting imperceptibly. This set-up fits hand-in-glove with the film’s thematic: the closure of identity is always unresolved.

Sunhi fails to take up an identity for herself from the ever-growing vastness of her self-knowledge, and so, like all Hong’s characters, falls into one that feels predestined. Sometimes Hong’s characters remind me of videogame NPCs. Travelling through scenes as minimal as levels in a platformer, these men and women are locked into an overriding pattern of choices. Only when something impinges on their set course, like the dreams in

Nobody’s Daughter Haewon, can these characters move beyond it. Otherwise they are confined to their predetermined paths, navigating through the same bars, coffee shops, love affairs. Professor Choi will continue to gaze toward the autumn sun, Jaehak will still live in his dingy apartment, and Haewon remains dreaming. Déjà vus, then, become disquieting. In a Hong film, something has always happened beforehand, a past relationship or trauma. Moving on from these scars, though, is nearly impossible. The attempt to do so results in repetition. Progress is always a matter of return. The tragedy of Hong’s characters failure to sense the immobility of their lives. They may be aware of it at times (“I’ve heard this before” is a frequent line in

Our Sunhi), but the loop on which they fall back on remains a straight line to their eyes.

Drunken lovers, one-night stands, and dreams-within-dreams are fundamental elements within Hong’s oeuvre as much as unmade beds, hypodermic needles, and revolutionary despair are in Philippe Garrel’s work. Hong is obviously less of a sensualist than Garrel and his films are taken for granted more often than the Frenchman’s, but in their constant development of a few motifs throughout their work both filmmakers could be considered as personal filmmakers --- a title forever attributed to Garrel, but rarely to Hong. An indication of this is that the films in their oeuvre, both Garrel’s and Hong’s, seem to answer to each other. Hong’s last three features (

In Another Country,

Nobody’s Daughter Haewon,

Our Sunhi) have female characters as leads. In all three films, all women are searching for an escape: from either the limits of the narrative itself (

In Another Country), relationships which are falling apart (

Haewon), or the closure of identification (

Sunhi). With an elastic wit and charm, Isabelle Huppert stretches beyond her boundaries to leave her trace behind three completely separate narratives. The only escape left for Haewon is a dream-within-a-dream. Sunhi leaves the three men behind and moseys off gracefully. Hong’s oeuvre may be a form of arthouse schematism, but the mysteries “beyond the image” which flood his films disallow such ruthlessness, as in the wonderful moment when the offscreen sound of door chimes melts into a woman’s singing voice emanating from an unseen radio.